QAnonvelopes: #Sustainability and the Big Foam conspiracy

You ever wonder if ASHREA is actually just a secret cabal of petrochemical companies who are trying to offset declining fossil fuel revenues with the sale of Styrofoam products and that they’re forcing us to buy more and more of them by continually jacking up R-value requirements under the guise of sustainability and energy efficiency?

You guys like poche, right?

No? Me neither. I’m just kidding. Mostly. I mean, I’m joking about the Big Foam conspiracy that I just made up (though I wouldn’t at all be surprised if this is a major lobbying effort that resembles the situation I described), but I do sometimes wonder if we’re going about sustainability from the wrong angle. Sometimes, at least.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m actually really passionate about sustainability. I don’t think it’s just another way to sell us stuff by appealing to our tree-hugging sensibilities (though I did just spring for a sweet pair of “made from recycled materials” Nike Cortezes with a cool knit upper and funky recycled foam midsoles, but I needed a new pair of sneakers anyway b/c my trusty Gazelles have a hole in the bottom that sucks water into them whenever I walk near a puddle). That exists, sure, but then maybe it should: sometimes we need to replace old stuff with new stuff, and it’s good to replace things with other things that are incrementally better when the time comes.That’s kind of the big question, though: when is that time? And what happens to the old stuff? We need to be more critical about what gets saved and what gets thrown away. Let’s think about cars, for example. Remember the Cash for Clunkers program? It was in 2009, and it allowed people to trade in vehicles for more fuel-efficient ones provided that the follow criteria were met:

• Vehicle must be less than 25 years old on the trade-in date.

• Only the purchase or 5-year minimum lease of new vehicles qualify.

• Generally, trade-in vehicles must get a weighted combined average rating of 18 or fewer miles per gallon (some very large pickup trucks and cargo vans have different requirements).

• Trade-in vehicles must be registered and insured continuously for the full year preceding the trade-in.

• Trade-in vehicles must be in driveable condition.

• The program requires the scrapping of the eligible trade-in vehicle and that the dealer discloses to the customer an estimate of the scrap value of the trade-in. The scrap value, however minimal, will be in addition to the rebate, and not in place of the rebate.• The new car bought under the plan must have a suggested retail price of no more than $45,000, and for passenger automobiles, the new vehicle must have a combined fuel economy value of at least 22 mpg US (11 L/100 km; 26 mpg imp).

Ok, so the program was, according to a bunch of reports, effective at slightly decreasing the average fuel consumption of the American vehicle, which is good. But think about the criteria: Who does this benefit? People who can afford to buy new cars. How does it work? They trade in their old, still functional car, and the dealer drains the oil out of the engine and replaces it with a sodium silicate solution, then runs the engine which causes it to seize. When an engine seizes, it means that the pistons and block (well, the cylinder sleeves, really, I guess, but whatever) have gotten so hot that they’ve fused themselves together. This means that the engine is destroyed and is also way harder to use for parts or even to recycle (aluminum block + steel cylinders stuck in it = frowny emojie).

This was to keep these old vehicles from getting back on the road, but consider this: how many people out there were priced out of this program? Look at the criteria. How many of those people had way shittier cars than the ones that were traded in and destroyed? How many people could have swapped their even-worse cars for slightly better cars, and how many more still could have used the parts from the destroyed engines to perform necessary repairs that would have made their cars cleaner and safer? Isn’t that way better for everyone?

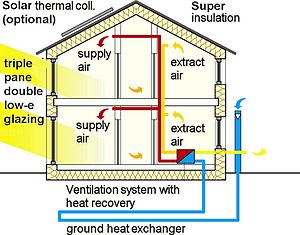

Which brings me back to the R-values thing. I think that there are many circumstances where stuff like superinsulation and geothermal systems are 1000% appropriate, but I also think we need to be reevaluating our expectations of comfort and the way we manage it. Why, for example, should anyone be expected to wear true business casual, much less a suit, to an air-conditioned office in the middle of summer. It’s dumb. It’s hot out and we’ve got to jack up the AC because we’re expected to wear coats and ties to work, and then we have to take jackets to restaurants in the summer because the AC is cranked for some reason.

It’s all dumb, and it’s all wasteful. Developing new, more efficient tech is important, sure, but I feel like we should also be changing our behaviors and reevaluating our cultural norms so that we’re also using that more efficient tech less. So I guess what I’m saying is that we need a shorts lobby?

Comments

Post a Comment